Getting Knowledge Work to Done

Mike Cohn at Mountain Goat Software takes on the idea of Getting to Done.

Mike Cohn at Mountain Goat Software takes on the idea of Getting to Done.

Cohn’s insightful post is focused on scrum as a software development process but applies to self-management and knowledge work. Let me explain how.

Cohn’s post considers four ways that completing work helps us. He defends the position that it is better to finish five tasks and leave five unstarted than it is to make partial progress on ten tasks. Here are the four ideas. I’ve changed the emphasis of the fourth and added a fifth:

Finishing gives faster feedback. In delivering software applications, feedback is critical. We get an idea what users want and try to build it. We think we’ve done a respectable job, but never really know until the users get their hands on that part of the application, use it, and let us know. Knowledge work is similar. We never really know how good a job we’ve done until we implement the new or improved process and measure the results or deliver the completed report and get feedback. Neither of these can be done with a partially finished knowledge work task.

Finishing gives faster payback. In software, an unfinished feature is similar to inventory and work-in-progress in a manufacturing plant. We have paid for the inputs, but cannot yet sell the product. Until we finish, we won’t get paid and we can’t cover the cost of the inputs. In knowledge work, we have used up some of our valuable attention, and perhaps our employer has paid for our time, but we don’t have anything that we can implement or deliver to recover those costs until we have finished the task.

Estimating progress on unfinished work is a hard problem. Software is well known for the “90% complete” problem. Software project managers have a running joke that programming tasks are “90% complete for 90% of the time”. Cohn’s post makes the point that this could be literally true in the programmer’s mind because as we make progress on a task, we find more detail about what needs to be done to actually complete the task. I believe this to be true of complex knowledge work tasks as well. Regardless, we are terrible at estimating how long things will take, particularly when the task is something we have never done before. On the other hand, we are great at knowing a task is unstarted, and decent at knowing when it is finished. In between, we are terrible at estimating how far we have come and how much we have left to do. And (see the next point) the more partially finished tasks we have, the worse we are at figuring out when they will all be done.

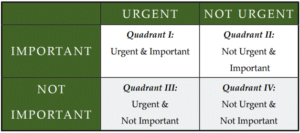

Work should be “not started” or “done” with nothing in between. Here, I’ll emphasize a different point than Cohn’s post. While we are working on a product, a software feature, or a knowledge work task, it is in a very complex state. A finished task is conceptually very simple; an unstarted task is slightly more complicated, but still relatively simple. A partially finished task is the most complex by far as we must keep track of the moving parts within the task.

Imagine a factory with lots of work-in-progress. When we stop work while Product A is unfinished, we must put it away somewhere, clean and reset the tools, and get out the plans/instructions for Product B. When we restart work on Product A, we must find where we put it away, figure out where we left off, take it to its next machine, and reset the tools. Only then can we get it finished and shipped. All these tasks are unproductive, and thus waste.

There is similar waste in “reloading” a complex knowledge work task. I’ll illustrate with a complex writing task. Imagine we’ve set aside a partially complete version of Report A to work on Report B. When we return to work on Report A, we must complete several steps just to get ready to move it along. We must find the right version and figure out the page where we left off. We must get out our supporting materials or refind a web page we are referring to. We must get into a similar mental state as we had when we left off. I call these steps “reloading” the task. This reloading may take seconds for a very simple task, but can take several minutes for a complex task. Also, reloading is a cognitively demanding, mistake-prone task, so it uses up some of the brainpower that we could use to complete the report. Finally, we know reloading is hard, so it gives us another reason to procrastinate and turn to simpler, less important work.

Finally, I’ll add a new point: The psychology of starting. We feel somewhat relieved when we’ve started a task. Depending on our work culture, reporting that we haven’t started may be associated with ignoring work. Therefore, we feel bad about not starting. So, it may be challenging to adopt the “not started or done” mindset. However, I guarantee that, as a boss, I’d rather have something complete than nothing. If you deliver five complete out of ten, at least I can move five projects along. If you deliver zero complete out of ten, I’m helpless. In addition, over time, the “not started or done” mindset will help your boss think hard about the priority of individual tasks. This will get the whole team working on the problem of having multiple number one priorities.

The expenses and challenges associated with work-in-progress are well known in the manufacturing world. Cohn’s post shows similar challenges in the world of agile software development. I hope I have made the point that work-in-progress is also expensive and challenging in everyday knowledge work. Get finished, or don’t start. Devote your attention to a single task, Get to Done what you can, and deliver it, even if some of your tasks make no progress.

I just finished reading

I just finished reading  Smart, capable people often struggle with one crucial aspect of knowledge work: planning. In my experience, clients resist planning for a number of reasons. Here are some of the most common.

Smart, capable people often struggle with one crucial aspect of knowledge work: planning. In my experience, clients resist planning for a number of reasons. Here are some of the most common.